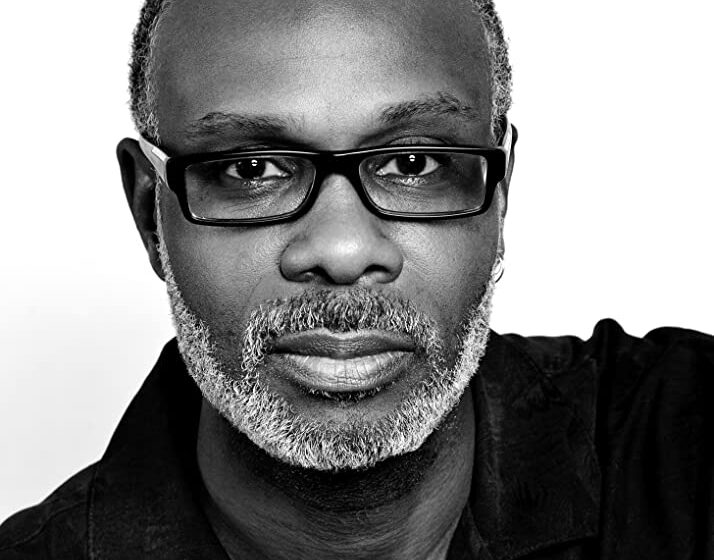

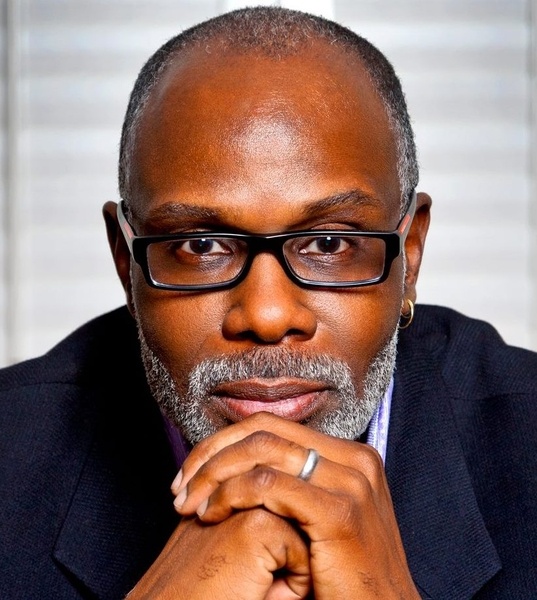

Cultural Healing with D. Channsin Berry of ‘Dark Girls 2’

It’s a solid five minutes before I reach to start the Zoom video. Amid a national pandemic, there is no safer way to interview, but for some reason, I’m still apprehensive. Maybe it’s because the subject matter is so close to home or maybe it’s because Mr. Berry turned down my offer to share my questions with him beforehand. A bold move, certainly one that isn’t the norm in my type of work, but as soon the conversation started I knew why. We both tested our audio for a bit, exchanged pleasantries, then entered into one of the most organic conversations I’ve ever had.

D. Channsin Berry is on a mission to heal a world that has been crying out for a very long time now, and over the span of an hour I found out exactly how he goes about achieving such an arduous task.

I saw that you were born in Newark, N.J., was that where you first decided that you wanted to be a filmmaker? What led to up to that point?

The film thing began, I guess, in East Orange, New Jersey. We lived with my aunt and my grandmother, my mother, my father and I. It was South 12th Street in Newark, N.J. as a matter of fact. I was born at the Presbyterian Hospital right around the corner, and I remember there was always music from the radio in the kitchen. There was something visual on the screen in the television room where my grandmother took her meals. Most of the day, I was on the record player, and I was fascinated by the images I saw on screen. Of course, it was black and white in those days.

My grandmother would watch all kinds of movies, Betty Davis and Clark Gable and Lana Turner… Humphrey Bogart. I grew up looking at those movies and one movie in particular. I remember it was storming, whether it would be Lena Horne and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Cab Calloway, it was a musical. So I think that’s where it was planted into me… that I would be somewhere between music and film.

So how did you decide between music and film?

It was always hard. It has always been hard, you know? Until recent years… I’m 60 plus, and I still go back and forth between music and film, film and music. You know, in my younger days, I started playing drums.

No! Really?

Yes, I was like seven years old. I started playing drums with my best friend, who lived around the corner, Eric Roundtree. He played congas and then took up the trumpet. The next thing I know, we started a band. We had another buddy of mine named Billy on bass, and a few people would come in and out on horns. So it was kind of a groove.

Well, it sounds like you developed quite the musical ear; now I’m curious as to how that translated into filmmaking. I’m sure you have sounds that you feel are more pleasant than others. How do you decide the difference between a good film and a great one?

There’s so many intricate components that go into making a film or a record period, you know? One thing has to fit and make sense. It’s like putting together a puzzle.

So to me, what makes a good film, I guess, is a great story. All of us have one. I think every single person on the planet has a good story. And I think every person on the planet is a documentary to me. I look at people as documentaries because everybody’s story is so unique.

I’m very interested in finding out how people got from point A to point B, so as I look at people, I look at their path from where they come to where they are now. It is unique and fascinating to me regardless of how they got there, but they did get there. That’s the story.

The script is the second thing and then, finding the actors, the right director, the right music to bring all of that to life, all of that smell to life, all of that substance, that mystery, that magic, that drama, that comedy… that love to life. It takes the combination of the right people at the right time for the right reasons to make the best film I think.

I really want to pinpoint something that you said, how you view people as documentaries. Were documentaries always your style of choice or did your perspective and viewing people as documentaries grow over time?

I think documentaries [have] always been the easiest thing for me to get into because I tried to go straight into feature films like everybody else– other filmmakers, young filmmakers. But I found it so hard because [there were] so many people involved. With the documentary, it could be just me and my camera person and my audio person.

That’s interesting…

And it was easy to shoot, easy to control because I did what I was passionate about. So I found a subject, a topic, an event, a person, a place or thing that I was passionate about and I would want to tell that story, that person’s story, that place’s story and what it came down to be was that I fell in love with–

Black people?

Oh, wow. I fall in love with black people. I fell in love with being me after understanding my purpose on the planet, and I understood my purpose on the planet when I was like nine years old. I knew what I wanted to be at nine years old. So film and music was the thing, but how could this little black boy from East New Jersey infuse those two things [in a way] that would make him happy? First, become a musician and then become a filmmaker.

I had moved from New Jersey to New York to Oakland, Calif. I was in radio for a while. I was in college at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., Piscataway, N.J. to be exact. [There] the fusion of music and film for me came when music videos started to happen. MTV evolved into what it became, and then here comes Michael Jackson– what incredible stories came from his songs. It just blew my mind up. Then there was Spike.

Shoutout to Spike! He’s my fellow Morehouse alumni. [laughs]

Ah yes! So when Spike did his first movie, I think that gave us (black people) the wind that we needed, [inspiration] for other African-American filmmakers to fly, because Spike had done it and Spike was from New York. I was from Jersey. You know, there was a Tri-State type of vibe that was going on in New York at the time. Even though I had gone and moved to Oakland, I still had that sense of New York and New Jersey about myself. So I was a little arrogant in a way when I came to California. Some people would tell me I need to slow down, like, “Where are you from?” I would say, “I’m sorry, I’m from the East coast. I’m from New Jersey/New York.” Then they [better] understood my aggressiveness.

You know, what’s the sense of hemming and hawing about it? Let’s get it done. Let’s just do it. In New Jersey, New York, we get it done. We start, and we finish, you know?

I definitely do, but I think it’s interesting that you say documentaries were the easiest for you. For the person that’s never been involved in it, they look like the most difficult. I was wondering how do you go about curating so many diverse personalities and perspectives to say what you’re looking to say? Do you go in with a list of must-haves, or is it completely organic?

My way of working is kind of organic and very unique from what I found. As always, I pick a subject, place, person, or thing that I have passion for. So we already know what that is– that’s black folk. And then, after that, I find an issue that people like us have a hard time talking about or dealing with. Then I go after that issue. I want to uncover the issue and the root of the issue, and then possibly try to find what the healing could look like in dealing with that particular issue. Is there healing available? What are the stories of so many people who have lived being black, and what part of the country? Can I get them to talk about where they’re from that is different from the struggle or the perception of others in the east coast, west coast versus the north and south?

Then there’s the pathway to success… all based on choices. Everything’s based on choices, and how one’s upbringing and your mental fortitude, your spirituality, the money you may or may not have… it’s all a part of how you look at things, how you approach certain things. As an artist, man, we use what we have, whatever. Because we see things differently and I think I’m an artist first before I’m anything. My eyes and my mind just work differently. What can I do with these colors of notes? What can I do with this narrative so different from everybody else? How can I pull my point across where everybody can get it, or most people can get it… get them thinking, and then get them healed.

When you speak on that healing, it’s known that your subjects are “black folks.” Being an African-American male myself, what is it about the black experience that you want viewers to understand? Is it just healing? Do you feel like the subject will switch eventually?

Well, let me answer the first question. What is it about the black experience that needs to be shared and for viewers to understand is that this is a culture of people, a tradition that is worthy of life expression, intellect, history, future, and presence. It’s worth life. Our existence is worth life. Our existence is the first existence; there’s a lot of power in that. This melanin in my skin represents so much, not just to Africa or to America or to the world, this skin color, this existence means much more to the universe because it’s a part of the universe, right? It’s made up of the universe. When I think about all things that are black, I always think about birth.

Wow.

When I think about things that are black, I always think about elegance. Death is black, but also death is life because that’s what life comes from—the dark. Black people’s skin is because of the sun and where we come from, the UV rays- that means something to us in terms of our health, our wellbeing, you know? It’s a gift. It’s precious. I own it, and in this comes gift-bearing to the planet as far as I’m concerned.

Yeah, I happen to be a man who happens to be black, who happens to be a child of God and the child of the universe. That means something. And I’m still here. That means something. Yeah. That means that I’m on a path and have been on the path that is, as far as I’m concerned, about helping other people understand who we are, and that we are rich in who we are, and giving who we are, and loving who we are. There’s humanity in this.

That’s beautiful and I think that really ties into my next question because as someone that understands this beauty and someone that wants others to appreciate it too, there is a narrative that black men specifically, do not support black women the way that black women support black men. Is your work an effort to change that? Or is this just a byproduct of what you’ve just said about your desire to share?

Black women for me are the mothers of civilization, as far as I’m concerned. Without black women, there would be no black men. And I’m not just saying that from a biological standpoint, from a living, standing, breathing boy to teenager to man, there would be no man without a black woman, but I do say this and I say this all the time in my lectures. We men have damn near destroyed the two things that give us life: the planet, and women. Until women are healed, we won’t be healed as men. That’s what I got.

If it wasn’t for black women, we would not have strives and businesses because, to me, they’ve always been the secret agent for us. They’ve been able to infiltrate the white male world without giving up a thing.

Really? I’ve never thought of it like that.

They’ve been able to bring that information back to us and say, “Look, honey, look, sweetheart, this is what’s going on. You should maneuver this way, and maybe you should dress this way. Got it?” In that way, we’ve been able to move in this thing called America without being killed, lynched, raped, shot, and run over too many times. But it wouldn’t be America. It wouldn’t be America without black women. So a lot of the things that I do are on black women– black men too– but I do a lot of things on black women also because I think it starts there. The healing starts there.

You know, they’ve been holding us up for a long, long time and been holding it down for a long, long time, which changes the dynamics of the relationship between black men and black women also. They were the ones to get the job. While we could not get those kinds of jobs or get any jobs at the time, the black women could always work inside the house where we were the brawn and the muscles who worked outside the house. They were inside the house, listening and getting all the information they possibly could and then teaching us how to maneuver to get through and basically survive.

When I was given this opportunity to speak to you, I went to some women that I know are very, very outspoken on these issues and their first question to me was, “how many women did you select for your production team?” Going back to the previous question. They felt that even when black men want to support them or explore the narrative about them, that sometimes it’s done just from a black male or male’s perspective. So they were curious, and they wanted me to ask the question of how have you made sure that their heart is shown with this film?

That, to me, is a very odd question because yes, I’m a black man who loves black women who decided to point a camera at some issues, because I wanted to become a better black man, a better brother, a better father, a better uncle, a better godfather, a better friend. So all of this is new to me. I came in with no preconceived notions that I wanted to know more, and when I got into talking to women over the last 15, 16 years of my projects, I found out that I knew nothing. But what I did find out after just listening– not trying to solve a problem as a man, but just listening– I found out that I became a better person, a better man, a better father, a better friend, better godfather, a better human being.

So I always have women around. My mother was one of my favorite people and she just passed away on Monday.

I’m so sorry to hear that.

Thank you…

I was raised around strong women and strong men from Georgia, Florida, and Maryland. Those were the ancestors that I come from. Not all of them were highly or formally educated people, but they all had homes. [They] made a way, and they all had drive. They all had talent. And they all believed in God. So that’s the way I was raised. So that got into me through my spirit as a little boy, and I kept it moving, never looked back.

I’ve tried to always do the right thing. I’ve been supported by the universe and by my ancestors and by people here on the planet, and [hopefully they] see me for what I am and for the work that I’m doing. So women are in my crews. Lots of women are in my crews. I listen, and I learn, but I love women. I love women not to abuse them. I love women because I respect them. People ask me that question all the time. You know, I had a woman curse me out one time. I’ll tell you what she said. She said, “Who the f*** do you think you are, doing a documentary about women? What are you? What do you know about women?”

I had to gather myself because I was so shocked because she said it in front of an audience and the audience gasped, you know?

What did you say?

Well, I just had to say, well… what can I say? I said I’m sorry, that’s your opinion. But I got to tell you that my mom’s a woman, my sisters are women. These are women, [including] my grandmother, and we all got great relationships. I’ve got nothing but good to say about them and what they’ve done for me in my life. I am the man that I am because of the women and the men in my life. I’ve always had balance in my life.

And the balance is not because there were more women or less men, or more men or less women. The balance they gave me [was] insight in the gem of self-esteem and my godly power, to take as my own.

With that balance, for men that are looking to follow in your footsteps, myself included, how do we respond or what advice would you give to anyone, specifically a black man, that is looking to support in a similar fashion to you?

First of all, I think you have to have a passion. Once again, it goes back to reverence, some type of strong love or belief or faith in what you’re doing in the story that you want to tell. It’s going to be slightly different because you’re a male, of course, you’re talking about females, you know, but if you’re truthful with yourself, it’s all about listening.

It’s all about listening and compassion. It’s kind of tapping into the creative side of your humanness, tearing down or moving apart, or moving aside the male energy that you have to be a little bit more compassionate. Understanding the senses of what women are feeling and talking about. We as men, we always want to, when a woman has a problem, we think that we need to come up with a solution to fix it.

How do you resist that?

The thing is, she has a problem. She’s dealing with the issue. Sometimes it’s not for a man to fix. Sometimes it was for a man to just sit there and listen, shut up and listen. Sometimes the best thing you can do is just shut up and listen, or just shut up and not say anything. [Listen to what] she’s saying, but just showing up, just being by her side. That’s enough.

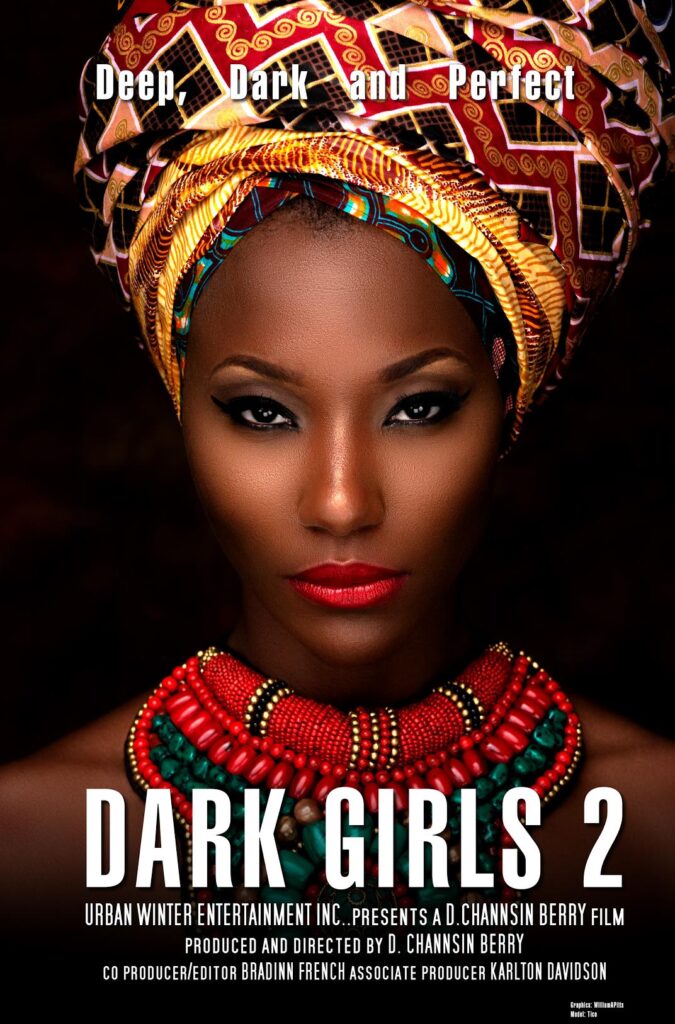

Thank you for that. Part of what I love about your films is the challenge in them. I saw in the captions for “Dark Girls 2” that you address the elephant of the room by simply asking, why do we need a second one? So let me ask, why in 2020 do we need a “Dark Girls 2”?

Because of two reasons… girls and female children are still in pain. Not all, but there are a lot of women and little girls who are still in pain and the proof of that is in the movie. When I went to a high school last year here in Los Angeles, in the Valley, I got together 31 girls from the ages of 14 to 17, all shades. I’d say it was the most emotional interview I’ve had in years. Listening to these babies in 2019 break down because colorism is still going on, people are still hurting people and we’ve got to stop. It’s gotten better since “Dark Girls” opened up the box because now women all over the world were able to have a conversation about being light or being dark in complexion and what that meant to them and their stories.

I see…

[This time] we opened up the box for healing to begin by having a conversation and recognizing that there is a problem, and there was a problem, and the problem still continues today. We have a lot more to talk about in “Dark Girls 2.” We’re talking about what healing could possibly look like now. That’s what we didn’t talk about in [the first film]– the healing and what that looks like for women of color around the world. Not just women here in America, but women in the islands, women in Africa, wherever there is a color issue… India, Japan, China, Brazil, and Ghana. There’s going to be an issue when there’s color involved and some places deal with two things. They dealt with colorism and classism, which was horrible.

You have those two isms together, but, colorism is still alive and well, man. You still get people who are bleaching their skin, who are willing to be lighter. In many cases, developing skin cancers, and then it has a question for me: Are you saying that God made a mistake? Is that what you’re saying to me, and you’re supposed to be Christian, Muslim, whatever, but you’re saying God, Allah, has made a mistake when he made you and that you can do better? He gave you that melanin in your skin to protect you because of where you live. Right? If you take that away from yourself, out of yourself, you will die.

Do you see a “Dark Girls 3” in the future?

No, not for me. Oh, no, no. I’ve moved on, I’m doing like four documentaries at once right now. I’m crazy. [laughs]

That was going to be my next question. What are you working on now?

It seems like I usually start a project when I’m in the middle of another project. That’s how I go. I’m crazy like that. I am working on a piece called “The Covered Mind”– it covers mental illness and the African-American community. Part one on children, part two on adults… [it’s] heavy, heavy, heavy… post-slave syndrome, post-traumatic slave syndrome, and the effect that it has on us mentally.

I’m talking about depression, talking about anxiety, talking about being bipolar, schizophrenia. Even when you get older, dealing with dementia and Alzheimer’s, so I’m talking a little bit about all of those things; interviewing women, girls, boys, men and grandparents all over the place. So that’s what I’m gearing up for right now– talking to professionals, black psychologists and psychiatrists around the country, around the world about their take… talking to geneticists, biologists, and genealogists about the chemical makeup, the biological makeup, and the cellular makeup of the DNA that comes from trauma. [Investigating] how that is passed down if at all passed down.

Then I’m working on “The Black Line: Profile of the African American Man Part 2,” where I’m talking to young folks like yourself about what it is to be a black man in America, which is so poignant right now. So yeah I’m working on that, and then I’m working on the Rufus and Chaka Khan documentary, and then I’m working on The Whispers documentary, the singing group called The Whispers. So I’m good. [laughs]

That is quite a plate. I know we live in a society that likes to focus on the negative, but what are some of those most memorable positive responses to your documentaries?

The deepest responses I’ve gotten, I’ve got more than one, is “You stopped me from killing myself.”

Wow.

Yeah. Every time I think about it I get teared up that God had put me in a place to reach out to someone, and that someone needed what God had given me to give to them at that particular time. It was the message that you can be saved. You can live and you can have a better life and thank God these women did not commit suicide. It’s very emotional.

How’s it feel to be a real lifesaver?

I don’t try to think about it. I don’t talk about it. The question doesn’t come up that often, but I try to avoid it. You caught me on a little emotional day, so yeah, it’s good when you can help. Somebody will help me. That’s for sure.

Well, as we prepare to close, how do we stay connected and stay tuned to your latest updates?

Facebook fan page is D. Channsin Berry. There is a Facebook page for Dark Girls 2. There is a website for the documentary, officialdarkgirls2.com. There is a website for just about all of my films.

But if you Google my name, D. Channsin Berry, you’ll be able to find me, and we can stay in contact. I’m on Instagram, you know that they got me on that… young folks got me on that. I don’t know what I’m doing, but you know, they tell me what to do. “Old man, do this.” They call me Papa Smurf now. [laughs]

I guess my last question is, who have been your biggest supporters and advocates for you on those low days? Who fills your tank?

God and my ancestors. I [also] have close friends, very close friends I can go to talk to that don’t judge me. They have no judgment and they listened to me and I go to them in council. They support me, man. They give me the juice, the knowledge, the wisdom that I’m seeking at that particular time, and I’m very, very, very blessed to have those kinds of people in my life.

2 Comments

The interview was very thought provoking. Great insight – looking forward to future films and upcoming events from D. Chansin Berry.

I must say that I rarely watch movies; however, this is one that I plan to watch. I enjoyed reading about Dr. Berry’s path to this production. We need motivations in positive ways, movies that challenges the mind; And offer solutions to some of our many problems. I should hope that Dr. Berry realizes that we have had enough crazy set & violence.